Chapter 2

Water Mains and Bloodlines

Cities rely upon dependable water to function and grow. San Francisco’s quest for and appropriation of fresh water from an ever-expanding hinterland is no different from that of Rome, New York, and other imperial cities. This chapter examines how closely related mining capital was to that quest as well as its relation to secretive dynastic fortunes through the ownership of urban and suburban real estate as well as vital sectors of the government and mass media.

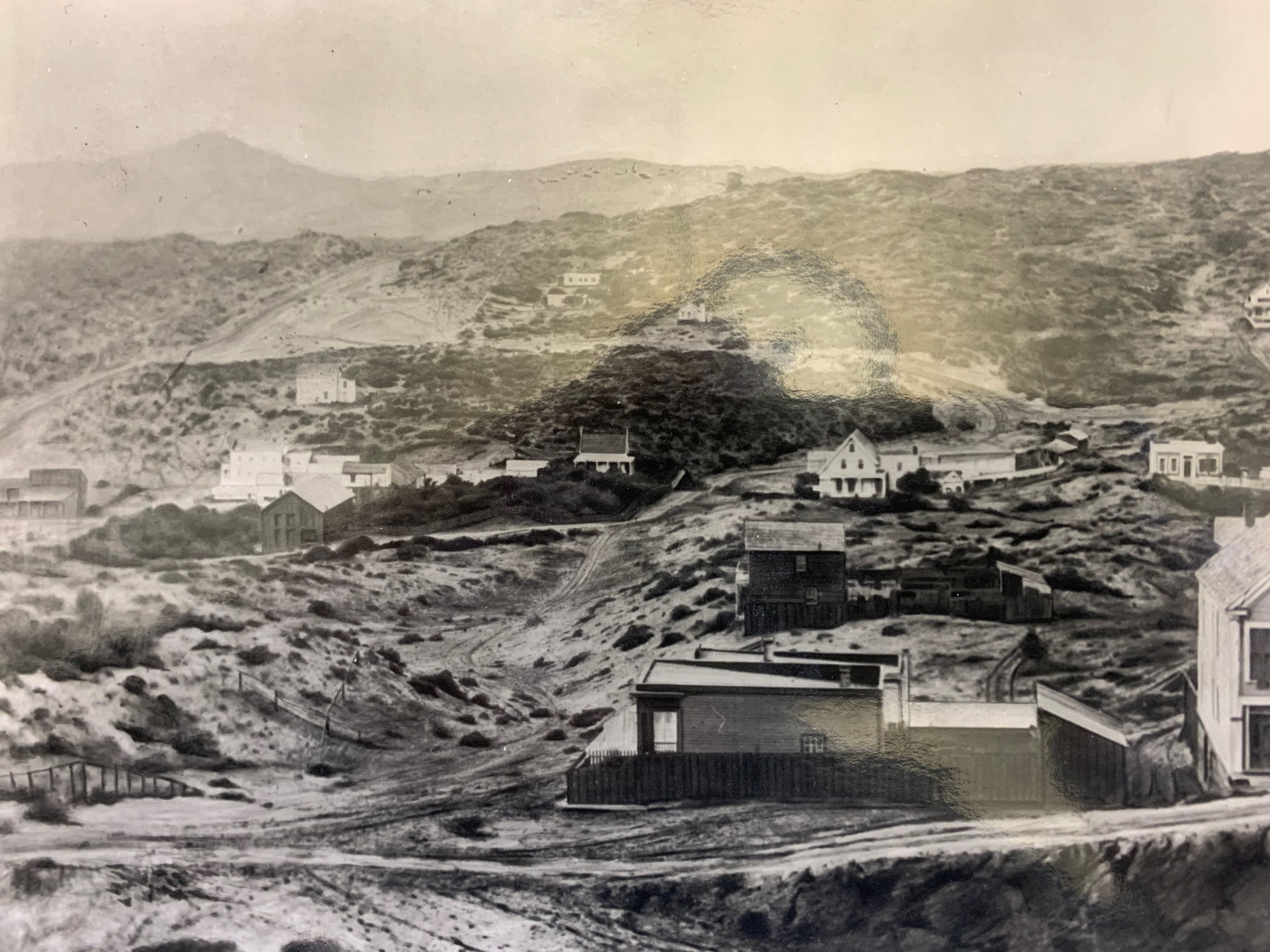

An 1857 view from the summit of Nob Hill facing southwest reveals the original dunescape of San Francisco, which supported too few creeks to comprise a municipal water supply. Courtesy Bancroft Library.

Selected notes

For more information on all the materials cited see the further reading page.

1. Pisani, From the Family Farm, 157. In exchange for condemnation rights, the legislature required the companies to provide public service at “reasonable rates” to be determined by administrative boards. Most communities neglected to form regulatory agencies, and those that did were easily bribed into compliance with whatever the companies’ directors found reasonable.

2. Von Schmidt’s prospectus sets the pattern of using urban capital (and later, voting blocs) to build water and power infrastructure that increases the property values of a select number of investors. His estimates of available supply were wildly extravagant but necessary to get backing for the scheme. Such catastrophic optimism for promotional purposes remains a common theme in Western water projects.

3. Ten years after his death, the Spring Valley Water Company dedicated a small memorial to Schussler at his Crystal Springs Dam. Its house organ claimed, “As long as San Francisco exists his fame will be perpetuated by his work.” Few major figures in the city’s history have been so thoroughly forgotten.

8. Sharon never visited Nevada during his single term in the Senate and rarely visited Washington, leaving Congress with one of its worst attendance and voting records.

9. According to banking historian Ira Cross, Sharon blackmailed Mills into contributing a million dollars to the rehabilitation fund, and then swindled Ralston’s creditors and widow. One of Ralston’s closest associates estimated that Ralston’s estate was worth not less than $ 15 million. See Cross, Financing an Empire, 1:405-7.

10. Lilley, “Early Career,” 67-69. When labor agitator Dennis Kearney, in 1878, accused Sharon of trying to sell his “rotten water works” to the city for $15 million, his audience expressed their wish to see him hanged by chanting, “Hemp, hemp, hemp!” Ibid., 94.

12. Upholding Hill’s claim a year earlier, Superior Court judge Sullivan declared the case “disgusting beyond description and tiresome almost beyond endurance,” as well as permeated with perjury. Lewis and Hall, Bonanza Inn, 151.

14. See Lizzie F Ralston et al. v William Sharon and]. D. Fry, California Superior Court, 1881, which strongly suggests that Mills, Sharon, and other directors, including Lizzie’s foster father, J. D. Fry, were parties to Ralston’s machinations. As late as 1894, Newlands countersued her to quit title to property valued in the millions.

15. Brother of San Francisco’s leading attorney and uncle of Newlands’s law partner Hall McAllister Jr., Ward invented the Social Register and coined the term “the Four Hundred” for those select few who fitted into Mrs. Astor’s ballroom.

16. To aid his cause, Newlands bought three leading newspapers, one each in Reno, Virginia City, and Winnemucca. Lilley, “Early Career,” 259.

20. Newlands’s other law partner, Judge James M. Allen, was a cousin through both men’s marriages into the Sharon clan. Judge Allen was a director of the Sharon Estate and of the Bank of California.

21. In 1888, Spring Valley’s president, Charles Webb Howard, boasted, “Owing more to the presence of these works than to any other cause, the assessed value of real estate, exclusive of improvements, is now four times as great as the total amount of the entire assessment roll at the time of commencement of the works.”

23. To my knowledge, no water scholars have deeply questioned the role of land speculation in San Francisco’s drive for hydraulic expansion, a charge from which Los Angeles is seldom spared. The marriage of water development and real estate in California predates the Los Angeles “grab” by decades, however. Mayors Sutro and Phelan in the 1890s were among the largest property owners in San Francisco; the visionary, populist, and Jewish Sutro remained an outsider in the local plutocracy, but banker Phelan, through his membership in and presidency of the Bohemian Club and allegiance to the Irish establishment, was an intimate and business associate of much of the Bay Area’s landed gentry. The use of publicly financed water to increase the value of private real estate continues today in the quiet domination by developers of municipal utility districts.

24. In 1905, Congress responded to developers by reducing Yosemite National Park by more than five hundred square miles. Hetch Hetchy Valley was not excluded at that time, but one of its chief selling points as a reservoir site was the protection offered to the watershed by the federal reservation surrounding it.

25. A socialist newspaper in 1914 accused Newlands and the Southern Pacific of profiting from the federal subsidy to the Newlands Project, but nothing came of it. Rowley, Reclaiming the Arid West, 165.

27. Newlands had acquired three hundred acres north of the city, which he planned to develop as an upscale community called Newlands Heights, and four city blocks that he hoped would become a civic center.

28. Thereafter, Tevis repeatedly attempted to sell his company to the cities of the eastern Bay Area.

29. Sentiment in the Bay Area overwhelmingly favored the dam. University of California president Benjamin Ide W heeler, an intimate of San Francisco’s business elite, made clear to his faculty that criticism of Hetch Hetchy would be most unwelcome, and that “John Muir is the man who stirred it all up.” M. Smith, Pacific Visions, 184.

30. As city attorney, Franklin K. Lane framed a new and more activist city charter in 1898 that required the city to own its own water supply.

31. Voters had repeatedly rejected the buyout as too expensive. The final price was the highest asked. The bond issue finally passed in 1928 after five tries, but because the city could not immediately sell the bonds, A.P. Giannini’s Bank of Italy agreed to buy them, as well as the Hetch Hetchy bonds. The directors of Spring Valley immediately appointed Giannini to the company’s board.

33. San Francisco hosted two spectacular fiftieth birthday parties for its very visible bridges in 1987. No comparable celebration marked the similar anniversary, in 1984, of the Hetch Hetchy system.

The Sunol Water Temple was designed in 1910 by Willis Polk as a tribute to the systems that fed ancient Rome. Photo: Gray Brechin.

“The Spring Valley Arcanum.” According to the satirical Wasp, the Spring Valley Water Company’s aqueduct from San Mateo County brought cholera to its customers in San Francisco and gold to those who owned the monopoly. In reality, cholera was more likely the result of San Franciscans’ reluctance to tax themselves appropriately so that they could build adequate sewers. The Wasp, March 21, 1885. Courtesy Bancroft Library.

Senator Sharon and mistress (or wife) Sarah Althea Hill frolic at William Ralston’s Belmont estate which Sharon acquired with the rest of his partner’s estate after Ralston's apparent suicide in 1875. The Wasp, April 26, 1884.

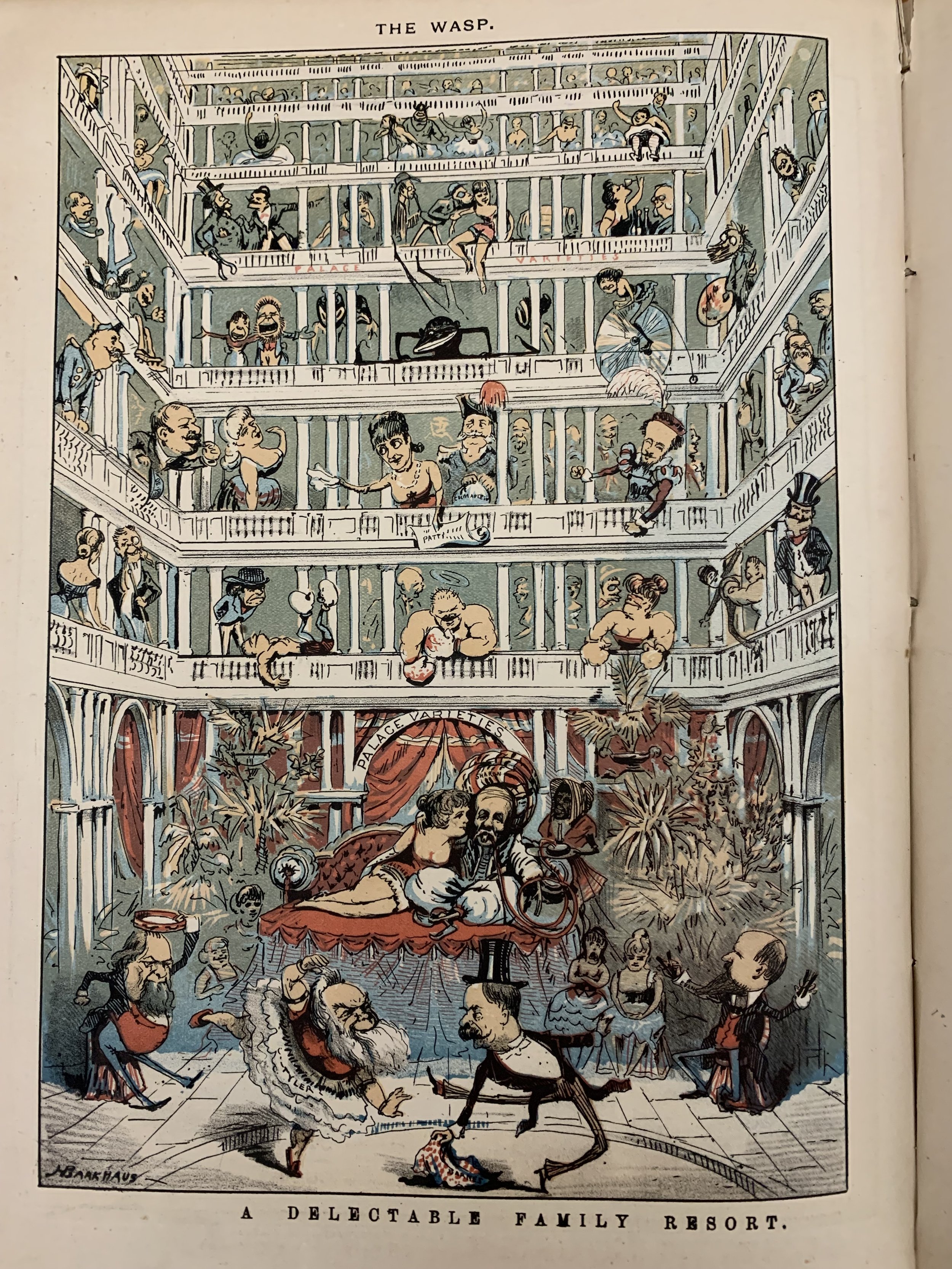

Senator Sharon as a dissolute pasha kicks back with Sarah Althea Hill in his luxurious Palace Hotel here caricatured as a riotous house of ill repute. The Wasp, April 5, 1884.

“Our Local Shoddiety.” Under the acidic editorship of Ambrose Bierce, The Wasp delighted in lancing the pretensions of San Francisco’s “best people.” Here, it suggests a monument in Golden Gate Park to celebrate the marriage of Lord Fermor-Hesketh to Flora Sharon, daughter of Senator William Sharon. The couple met in the senator’s Palace Hotel, here likened to a white elephant. At the base of the shaft, hogs revel at Sharon’s Belmont estate. The Wasp, January 15, 1881. Courtesy Bancroft Library.

“Come On In The Waters Just Fine.” San Francisco welcomes investors, manufacturers, and home-seekers with the promise of cheap and plentiful water from Hetch Hetchy the day after receiving a congressional variance to dam the valley in Yosemite National Park. San Francisco Examiner, December 20, 1913.