Chapter 1

The Pyramid of Mining

Mining is explained as the foundation and paradigm of urban growth and extractive imperialism throughout history with San Francisco as its modern exemplar of how the connection works.

Those who own and run both cities and mines mythologize the industry to their own benefit. Mining’s intimate connection with militarism, metallurgy, mechanism, and finance is visualized as an inverted pyramid that forces technological innovation, especially that which raises the value of urban land while its costs are passed downwind, downstream, and downtime.

The technological innovations forced by the difficulties of gutting Nevada’s Comstock Lode may have contributed to the invention of the skyscraper; such buildings not only define the skylines of major cities today but have been instrumental in further raising the value of urban soil for those who own it.

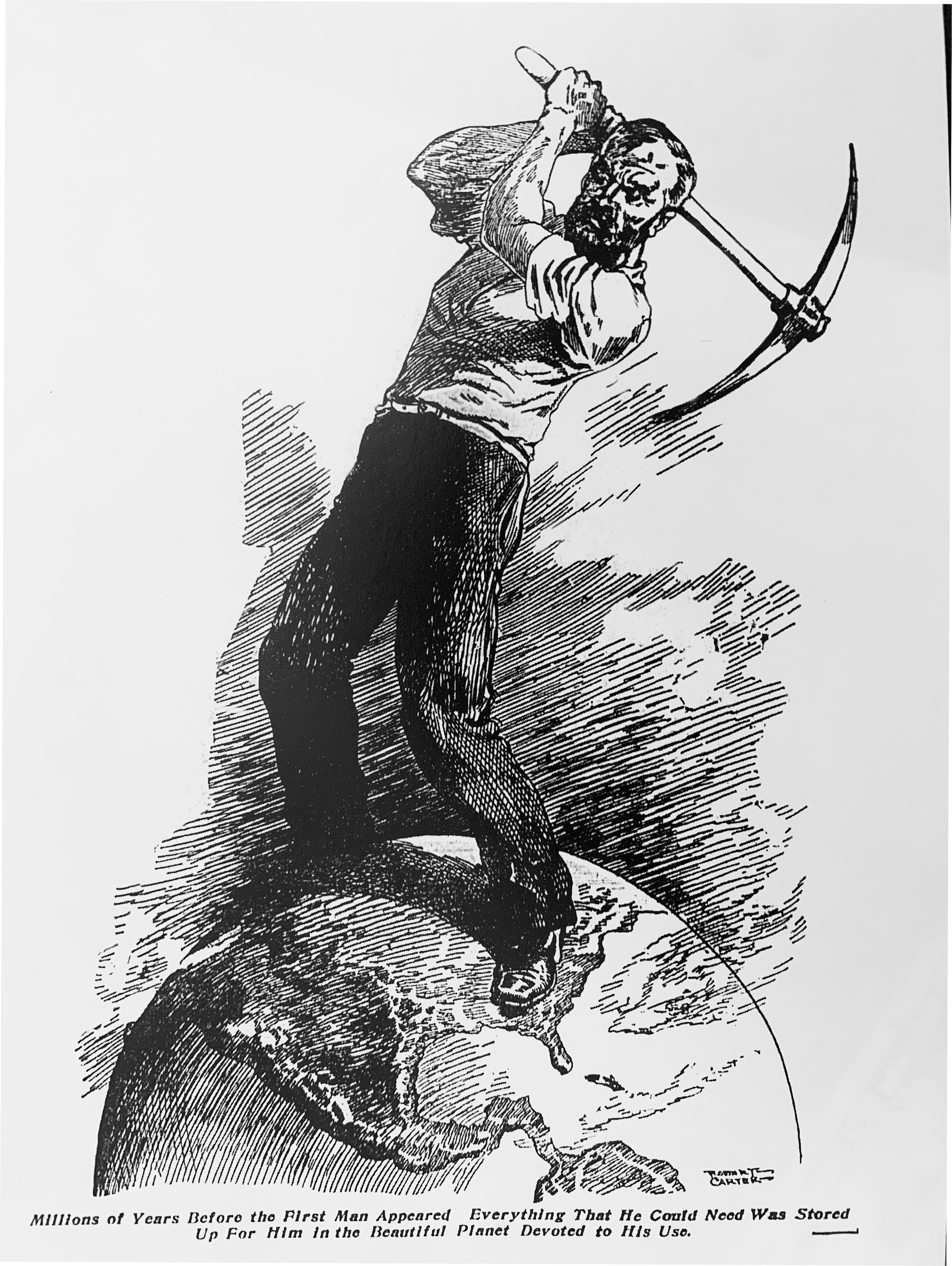

“Man’s Great Storehouse of Wealth.” A graphic in the Hearst newspapers celebrates mining as a violent assault upon the “Beautiful Planet Devoted to His Use.” San Francisco Examiner, February 8, I907.

Selected notes

It has not been possible to replicate the context of each note. For context, please refer if possible to the print edition. For more information on all the materials cited see the further reading page.

The invisible pyramid

2. Mumford first stated this thesis in his Technics and Civilization, and continued to develop it with greater urgency after Hiroshima. In The Pentagon of Power, Mumford proposed that the Megamachine of the ancient theocracies had returned in modern times, fueled by a literally blind faith in technology. The “ecocide” inflicted on Vietnam, Mumford felt, was only a concentrated version of what the Megamachine was progressively accomplishing globally in what was erroneously called “peacetime.”

The age of discovery, conquest, and Fugger

4. Of the English lords who sold arms to the Spanish armada and to pirates that harried British shipping, Thomas Rickard wrote, “As in modern days, the munitions-makers were not scrupulous as to whom they sold, and were not above doing business with the probable enemies of their own country.” Man and Metals, 889. The Iran-Contra scandal provided the public with a brief glimpse of a pattern of “patriotic treachery” as old as the Pyramid of Mining itself. I take up this theme in subsequent chapters.

De Re Metallica

6. Rickard notes that “Laurium, like most mining districts, was denuded of its trees at an early date. Today only a few stunted pines survive, but in the spring, wildflowers and herbs give a brief touch of beauty to the dreary landscape of this forlorn part of the ancient world” (emphasis added). Romance of Mining, 92.

7. Cronon, Nature’s Metropolis. While Cronon masterfully analyzes imperial Chicago’s environmental impact upon the Midwest, he gives scant attention to the coal, iron, and copper mining that enabled its leaders to exert their dominion, or to those leaders’ considerable investments in mining and its collateral activities.

A promised land plundered

11. As a former president of the Pioneers, Thomas Larkin proposed later in his life that a “first-class” membership should be created for those few who (like himself) had arrived prior to July 7, 1846, the date of California’s initial separation from Mexico. The Society compromised by establishing a first-class membership for those who had arrived prior to 1 849. Mere forty-niners thus became the demielect.

13. Property in California was concentrated in a remarkably brief period by those who arrived first and with capital, knowledge of the law, and a useful degree of ruthlessness. In the 1850s, as much as 80 percent of the personal and real property in San Francisco was owned by less than 5 percent of the city’s male workforce. The degree of monopoly in rural counties was even more extreme. See Issel and Cherny, San Francisco, 1865-1932, 16.

The Sierra Nevada flayed

15. De Quille, Big Bonanza, 174-79. The effects of mining are being felt to this day; forest managers credit the sudden transition from pine to fir following logging in the nineteenth century for the widespread death of drought-stressed trees in the Tahoe Basin. See “Dying Tahoe Trees Blamed on Mining,” Carson City Appeal, September 27, 1994.

Halting hydraulicking

16. B. Taylor, “On Leaving California,” Poetical Works, 92-93.

Mining engineers as heralds of empire

18. J. H. Hammond, Autobiography. One colleague referred to Hammond as “vain, loud mouthed, and a blowheart [sic],” while William Wallace Mein said that Hammond claimed the experiences of other engineers as his own and that his Autobiography was “full of lies.” Spence, Mining Engineers, 324, 336.

19. When Mills’s daughter Elizabeth married Whitelaw Reid, publisher of the New York Tribune, his family took over the nation’s most influential newspaper. Reid himself was an unsuccessful vice presidential candidate and an ambassador to England. Mills’s son, Ogden, married into the landed aristocracy of the Hudson River valley and his son became Herbert Hoover’s Secretary of the Treasury. The banker’s granddaughters married into the English nobility and Pittsburgh steel. The Mills and Hammond families joined to finance the transnational Milham Exploration Company.

20. Smith was associated with Edmund De Crano, a former miner and broker on the San Francisco Stock and Exchange Board. In addition to South African mines, Smith’s connections included the Alaska Treadwell, Anaconda, and other leading mining companies. In 1890, he helped to found and finance the Central London Railway. For the California connection, see A. F. Williams, Some Dreams Come True; and Rickard, ed., Interviews with Mining Engineers, especially the interview with Henry Perkins.

21. Gardner F. Williams, whom Smith also pulled into the Exploration Company, became manager of the DeBeers company’s diamond mines at Kimberley. Williams’s daughter married another Californian, William Wallace Mein, the manager of the Robinson Gold Mines in Johannesburg. Their descendants in turn merged with other Western dynasties and continue at the core of San Francisco society today. Gardner Mein founded the San Francisco society monthly the Nob Hill Gazette, whose motto is “Not just an address but an attitude.”

Enduring attitudes

25. Olmsted was not alone. An unnamed writer in the Overland Monthly observed that “[San Francisco’s] merchant princes are stock-jobbers, and her capitalists are land and mine and wildcat speculators; Shylock sitting at the receipt of customs, and selfishness forging the chains of the blind votaries of chance!” “City at the Golden Gate.”

26. For example, the former CEO of Louisiana-Pacific Corporation Harry Merlo has been quoted as saying of the company’s northern California oldgrowth forests, “We need everything that’s out there. We log to infinity. Because we need it all. It’s ours. It’s out there, and we need it all. Now.” Ridgeway, “Logging to Infinity,” 20.

Financial districts as inverted minescapes

27. The Hallidie Building is located at 130 Sutter Street.

28. Scots master mechanic Joseph A. Moore of the Risdon Iron Works claimed to be the inventor of the hydraulic lift elevator, which he derived from pumps developed for the Comstock mines. Moore said that he took or sent the plans for the elevator to New York and Glasgow. He attempted to profit from the invention’s possibilities for raising the value of urban real estate, but apparently failed to raise the necessary capital. See Joseph Moore, “Dictation of Joseph Moore,” 1888[? ], collection of Hubert Howe Bancroft. Architect Daniel Burnham, one of the inventors of the Chicago skyscraper, visited and worked in the Nevada mines in 1868 and 1869.

29. Deidesheimer did not patent his invention and he died broke. Spence credits it with being among the most valuable innovations in mining history.

30. John Hays Hammond described the ten-story office block that Mills completed across from the New York Stock Exchange in 1883 as the most impressive skyscraper of its day. Though it lacked a true skeletal structure, it had its own electrical generating plant, more than five thousand electric lights, and ten elevators, as well as a remarkably modern articulation. When the second Mills Building was opened in San Francisco in 1891, it boasted the first entirely steel frame of any structure in that city. George Post designed the former, Burnham and Root the latter.

31. William Randolph Hearst to George Hearst, 29 January 1885, Phoebe Apperson Hearst papers, box 63, file ‘‘To George Hearst.”

Cross section of Nevada’s Comstock Lode with revolutionary Deidesheimer square set. Courtesy Bancroft Library.

In “The Weapons of the Argonauts”, Carleton Watkins created a still life of the kind of primitive mining tools used during the brief period before the industry became high tech and capital-intensive. Courtesy Bancroft Library.

River mining deforested large sections of the Sierra Nevada for the lumber necessary to divert rivers into flumes, like the one in this photo by Carleton Watkins. Such operations were not enterprises of the independent miners of popular mythology but rather required city-based banks and exchanges to raise capital. Courtesy Bancroft Library.

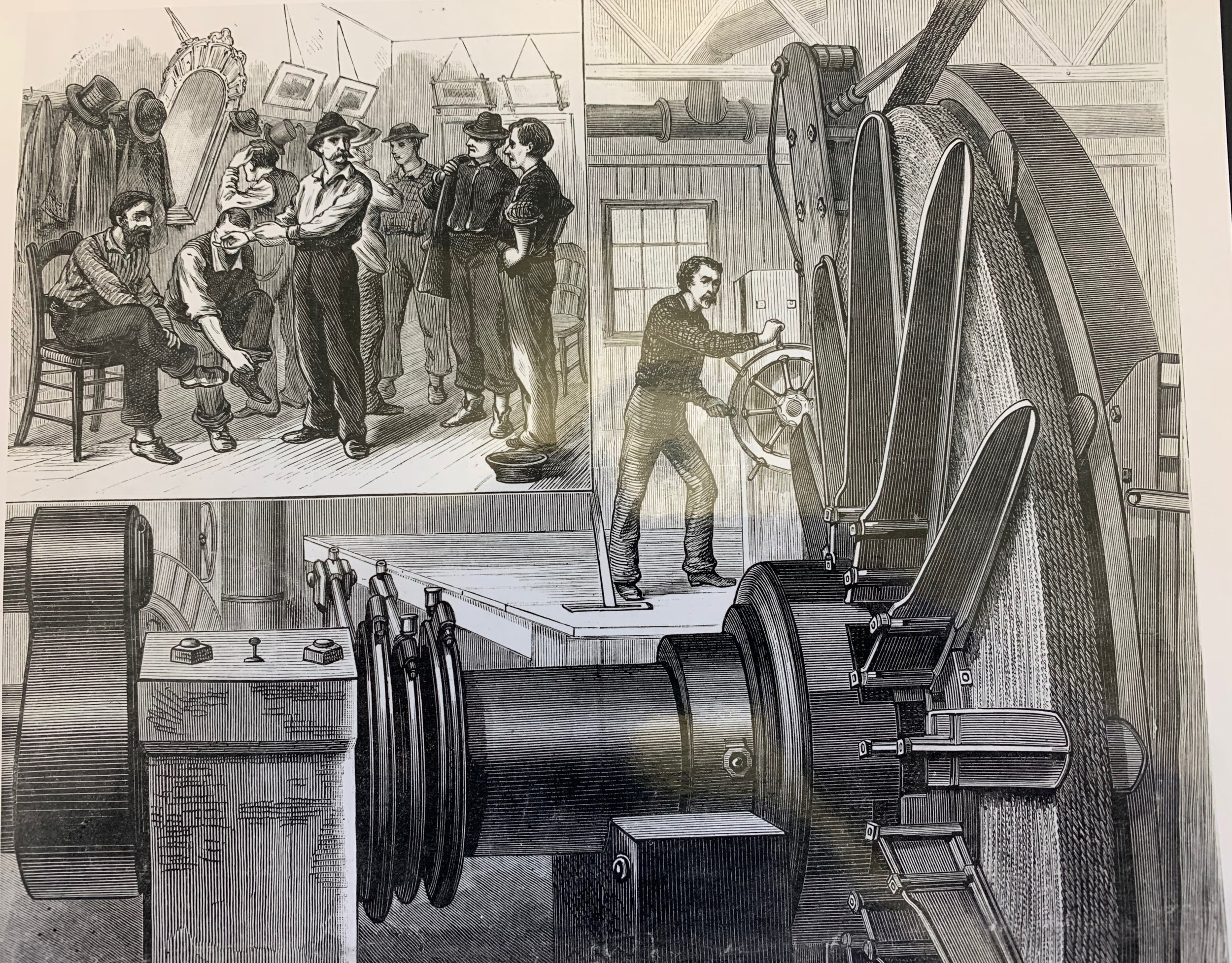

The Comstock mines proved so rich, deep, and hot that they forced the development of mining technology. Steam-powered iron flywheels for high-speed safety elevators with iron cables were manufactured in San Francisco’s iron district located south of Market Street. Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, March 9, 1878. Courtesy Nevada Historical Society.

The latest hoisting technology in 1556, illustrated in Agricola’s De Re Metallica, was a wooden undershot wheel used to pump water in German and Bohemian mines

The Shell Building rises behind Douglas Tilden’s Mechanics’ Monument, which honors San Francisco’s ironworkers. The steel-frame skyscraper bears a close resemblance to the Deidesheimer square set translated into metal. It uses much the same technology for vertical transportation, communication, and life support as did the Comstock mines. Courtesy San Francisco Public Library.

California as a mining goddess cracks the Earth as if it were an egg to fry in a gold pan. San Francisco Chronicle, December 31, 1911.